- INGRID BERGMAN “Murder on the Orient Express”

- VALENTINA CORTESE “Day for Night”

- MADELINE KAHN “Blazing Saddles”

- DIANE LADD “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore”

- TALIA SHIRE “The Godfather Part II”

Movies, Actresses, Actors & Other Things... A collaborative project between Canadian Ken & StinkyLulu.

Sunday, November 26, 2006

1974 : The Overlooked

Over at StinkyLulu’s (where supporting actresses get top billing) 74 is the magic number this month - 1974 to be precise. Which means the smackdowners have weighed in on another crop of nominees:

1974 : The Overlooked - WENDY HILLER & RACHEL ROBERTS in “Murder on the Orient Express”

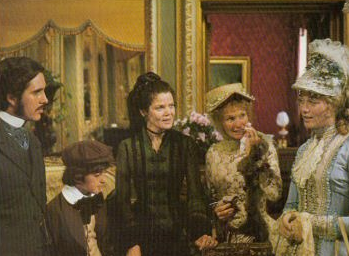

The picture’s distinguished by sensational costumes, irresistible title music (a wry fusion of 30’s glamour and glorious Rogers Williams style piano kitsch) and the sheer celebrity of its cast. A few of these cast members contribute delicious vignettes. Vanessa Redgrave puts a playfully subversive spin on her character, getting substantial mileage out of sunny impertinence. And in a role someone else might have phoned in, Jean-Pierrre Cassel scatters little flecks of gold with his melancholy charm. Then there’s Wendy Hiller.

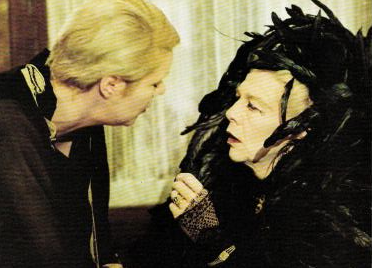

The picture’s distinguished by sensational costumes, irresistible title music (a wry fusion of 30’s glamour and glorious Rogers Williams style piano kitsch) and the sheer celebrity of its cast. A few of these cast members contribute delicious vignettes. Vanessa Redgrave puts a playfully subversive spin on her character, getting substantial mileage out of sunny impertinence. And in a role someone else might have phoned in, Jean-Pierrre Cassel scatters little flecks of gold with his melancholy charm. Then there’s Wendy Hiller. Her Princess Dragimiroff is a creature of magnificently constipated grandeur. What with the elaborate headgear and the everpresent suggestion of hatpins, whale-bone corsets and industrial strength girdles, it’s sometimes hard to say where Tony Walton’s marvelous costuming ends and Hiller’s performance begins. She’s a regal symphony in black, moving through the proceedings like some stately float in a royal funeral procession. Armed with an indeterminate but imposing accent, she seems to be squeezing her words out of a particularly stubborn tooth-paste tube. The princess’ response, when asked about her chronic failure to smile:

Her Princess Dragimiroff is a creature of magnificently constipated grandeur. What with the elaborate headgear and the everpresent suggestion of hatpins, whale-bone corsets and industrial strength girdles, it’s sometimes hard to say where Tony Walton’s marvelous costuming ends and Hiller’s performance begins. She’s a regal symphony in black, moving through the proceedings like some stately float in a royal funeral procession. Armed with an indeterminate but imposing accent, she seems to be squeezing her words out of a particularly stubborn tooth-paste tube. The princess’ response, when asked about her chronic failure to smile:“My …dok … tor… has … advised … against …it.”

Though never less than dignified, she’s also a riot – Edith Evans struggling to contain her inner Don Rickles. When Lauren Bacall complains that a man entered her compartment to gain access to the adjoining one, Dragimiroff pipes up from the sidelines with antique solemnity:

“I … can … think .. of … no … other … reason.”

And, oh yes, when the princess finally does bestow one of those medically prohibited smiles on us, Hiller makes very sure it’s a thing of beauty.

She doesn’t actually wear a monocle or smoke a cigar. She doesn’t have to. Rachel Roberts can always summon up everything she needs from deep within her. She’s that good. Her decidedly butch Fraulein Hildegarde Schmidt is an old school German who stops just short of clicking her heels. A walking catalogue of repressions, she expends equal amounts of iron-clad energy keeping a lid on her sexual inclinations AND her sentimental streak. There’s always so much Fraulein’s trying to keep from happening that a whole lot’s constantly happening. She’s all about discipline – loves to please her superiors. Full marks for that smile she lets slip when Poirot compliments her on her cooking. The accent’s spot-on, the characterization solid – no sense of a skit here. She’s amusing, of course. But affecting too. As Dragimiroff’s maid, she plays most of her scenes with Hiller. And watching these two acting titanesses match skills is giddy gratifying fun. In 1978 the Christie cycle offered another engaging upstairs/downstairs duo – with the unexpectedly effective pairing of Bette Davis and Maggie Smith. Those two presented a quite different – but equally diverting – dynamic.

She doesn’t actually wear a monocle or smoke a cigar. She doesn’t have to. Rachel Roberts can always summon up everything she needs from deep within her. She’s that good. Her decidedly butch Fraulein Hildegarde Schmidt is an old school German who stops just short of clicking her heels. A walking catalogue of repressions, she expends equal amounts of iron-clad energy keeping a lid on her sexual inclinations AND her sentimental streak. There’s always so much Fraulein’s trying to keep from happening that a whole lot’s constantly happening. She’s all about discipline – loves to please her superiors. Full marks for that smile she lets slip when Poirot compliments her on her cooking. The accent’s spot-on, the characterization solid – no sense of a skit here. She’s amusing, of course. But affecting too. As Dragimiroff’s maid, she plays most of her scenes with Hiller. And watching these two acting titanesses match skills is giddy gratifying fun. In 1978 the Christie cycle offered another engaging upstairs/downstairs duo – with the unexpectedly effective pairing of Bette Davis and Maggie Smith. Those two presented a quite different – but equally diverting – dynamic.

1974 : The Overlooked - MILDRED NATWICK in “Daisy Miller”

Of course, it’s an ordeal to watch Cybill Shepherd clobbering her way through Henry James. A giant toadstool of a performance. And even in the lovely 19th century gowns, she still looks like a linebacker. (Where, oh where, was Leigh Taylor-Young when we needed her?). The film’s hard-pressed to survive a disastrous Daisy. But it manages. Because “Daisy Miller” has so many other things going for it. Fine script, handsome production, excellent leading man (Barry Brown) and bell-ringing supporting turns from a pair of illustrious ladies.

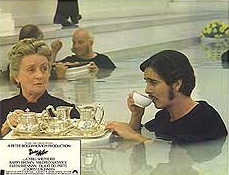

The marvelous Mildred Natwick was nothing if not versatile. A strong dramatic actress, she could also dither with the best of them. Teamed with Charles Boyer in “Barefoot in the Park” (1967), she proved to be his most deliciously amusing partner since Irene Dunne. In “Daisy Miller” we first encounter her up to her elegant (and fully clothed) elbows in the baths with a silver tea service floating preposterously in front of her. She’s Mrs. Costello, a blueblood through and through, absolutely encoded with a complex system of societal do’s and don’ts which she maintains rigorously. To her, these principles represent the natural order of things – and guided by them, she regards herself as capable of recognizing decorum in all its facets. And – just as importantly – the lack of it. Her entire manner suggests a weary acceptance of the fact that most people WILL not and CANnot understand what’s proper. Mrs. Costello’s idea of noblesse oblige is pretty much summed up in her cool appraisal of the Miller clan:

The marvelous Mildred Natwick was nothing if not versatile. A strong dramatic actress, she could also dither with the best of them. Teamed with Charles Boyer in “Barefoot in the Park” (1967), she proved to be his most deliciously amusing partner since Irene Dunne. In “Daisy Miller” we first encounter her up to her elegant (and fully clothed) elbows in the baths with a silver tea service floating preposterously in front of her. She’s Mrs. Costello, a blueblood through and through, absolutely encoded with a complex system of societal do’s and don’ts which she maintains rigorously. To her, these principles represent the natural order of things – and guided by them, she regards herself as capable of recognizing decorum in all its facets. And – just as importantly – the lack of it. Her entire manner suggests a weary acceptance of the fact that most people WILL not and CANnot understand what’s proper. Mrs. Costello’s idea of noblesse oblige is pretty much summed up in her cool appraisal of the Miller clan:To her, the concept of upward mobility stands in utter – and idiotic – defiance of the laws of – not just propriety – but gravity. The lady sees no need to deliberate about things that are self-evident. But, for all Mrs. Costello’s inflexibility, Natwick makes our experience with her quite pleasant. And narrow though her viewpoint may be, she does make some awfully penetrating observations. The lady doles out her dialogue one silver spoonful at a time – never giving us quite as much as we want. Thanks to Henry James, Mrs. Costello has a way with words. Which is the very least one can say in praise of Mildred Natwick.

1974 : The Overlooked - EILEEN BRENNAN in “Daisy Miller”

Had she been around then, Eileen Brennan’s expressive face – deep, dark eyes, opulent mouth, intoxicating sly-boots energy – might well have secured her stardom in silent films. Because she came later, we were lucky enough to hear her speak. As Mrs. Walker, elegant drawing-room piranha, she uses that voice to full effect. It’s pure India ink – rich, dark, luxurious, quite indelible. Her makeup is subdued but witchy, the total look suggesting a sort of gill-breathing Janis Paige. Unsettling, but just try to look away. She swims in an elite stream - an expert on every ripple in it. No stranger, one suspects, to its murkier depths. Certainly aware of its limits. And singularly displeased with anyone who openly swims against the current.

Had she been around then, Eileen Brennan’s expressive face – deep, dark eyes, opulent mouth, intoxicating sly-boots energy – might well have secured her stardom in silent films. Because she came later, we were lucky enough to hear her speak. As Mrs. Walker, elegant drawing-room piranha, she uses that voice to full effect. It’s pure India ink – rich, dark, luxurious, quite indelible. Her makeup is subdued but witchy, the total look suggesting a sort of gill-breathing Janis Paige. Unsettling, but just try to look away. She swims in an elite stream - an expert on every ripple in it. No stranger, one suspects, to its murkier depths. Certainly aware of its limits. And singularly displeased with anyone who openly swims against the current. Mrs. Walker is society to her fingertips. But, unlike Mrs. Costello, doesn’t feel totally secure in her position. Her status depends on a carefully constructed house of cards, not one of which must be removed or even jostled. Mrs. Costello’s closet may be skeleton-free. Mrs. Walker’s probably not. There are indications of a taste for illicit adventure. The near-constant presence of young blonde Nicholas Jones in her vicinity creates an impression, shall we say. One that tiptoes past the ambiguous into the neighborhood of the incriminating. She also casts a more than covetous eye on Mr. Winterbourne. Watch her speak to him. She seems to want to gobble him up. These appetites tend to jeopardize the delicate status quo. Mrs. Walker patrols the social scene, sensitive to the slightest seismic shift, knowing it could expose her foibles and put her at risk.

Mrs. Walker is society to her fingertips. But, unlike Mrs. Costello, doesn’t feel totally secure in her position. Her status depends on a carefully constructed house of cards, not one of which must be removed or even jostled. Mrs. Costello’s closet may be skeleton-free. Mrs. Walker’s probably not. There are indications of a taste for illicit adventure. The near-constant presence of young blonde Nicholas Jones in her vicinity creates an impression, shall we say. One that tiptoes past the ambiguous into the neighborhood of the incriminating. She also casts a more than covetous eye on Mr. Winterbourne. Watch her speak to him. She seems to want to gobble him up. These appetites tend to jeopardize the delicate status quo. Mrs. Walker patrols the social scene, sensitive to the slightest seismic shift, knowing it could expose her foibles and put her at risk.Daisy Miller presents a threat – on several levels – to Mrs. Walker’s peace of mind. She’s young and pretty. Check. Winterbourne’s evidently smitten. Double check. She’s also a wild card. Doesn’t play by the rules. Rocks the boat in unexpected ways. Triple check. Even Mrs. Walker’s smooth expertise as a hostess is jangled by Daisy’s pop-up non-sequiturs. Not to mention the willy-nilly antics of Daisy’s mother and brother. The whole family interferes with the rhythm of things – and the predictable rhythm of society is what Mrs. Walker depends on.

Brennan’s role climaxes with the carriage scene. Ostensibly, she’s out to save Daisy from compromising herself. In fact, she’s in hot pursuit of Winterbourne, propelled, in part, by that urge that makes us want to actually witness the thing that’s most galling to us. And of course, she means to stop Daisy - come Hell or high water – from once more rocking the boat. But Daisy’s pert-mouthed indifference, coupled with Winterbourne’s obvious infatuation, are entirely too much for Mrs. Walker. When Daisy WILL not be cowed, the lady’s speech escalates from cool reasoning to barely contained fury. By the end of the scene we can practically see smoke pouring out of her. With the weight of society behind her, Mrs. Walker can definitely exert a certain dangerous power – at least on a social creature like Winterbourne. She absolutely impels him away from Daisy and into her carriage. There’s very little she won’t consider doing – but only so much she CAN do without upsetting her own apple-cart. Brennan does it all up with venomous flourish. A study in seething –but very well-groomed – frustration.

Brennan’s role climaxes with the carriage scene. Ostensibly, she’s out to save Daisy from compromising herself. In fact, she’s in hot pursuit of Winterbourne, propelled, in part, by that urge that makes us want to actually witness the thing that’s most galling to us. And of course, she means to stop Daisy - come Hell or high water – from once more rocking the boat. But Daisy’s pert-mouthed indifference, coupled with Winterbourne’s obvious infatuation, are entirely too much for Mrs. Walker. When Daisy WILL not be cowed, the lady’s speech escalates from cool reasoning to barely contained fury. By the end of the scene we can practically see smoke pouring out of her. With the weight of society behind her, Mrs. Walker can definitely exert a certain dangerous power – at least on a social creature like Winterbourne. She absolutely impels him away from Daisy and into her carriage. There’s very little she won’t consider doing – but only so much she CAN do without upsetting her own apple-cart. Brennan does it all up with venomous flourish. A study in seething –but very well-groomed – frustration.She does return at the end for a prominent appearance at the funeral. But she’s not there to mourn. Rather, to put a period on Daisy’s inconvenient story. Another hole in the dike has been successfully plugged. To Mrs. Walker, Daisy’s death is not a tragedy. Just another confirmation that failure to keep up appearances leads to inevitable doom. Actual – and more importantly – social.

1974 : The Overlooked - MADELINE KAHN in “Young Frankenstein”

I find a natural resistance rising within me when I see “Blazing Saddles” referred to as an important achievement. I guess it’s because that kind of implies a substantial amount of artistic merit. The picture DID thumb its nose at a lot of longstanding taboos – and proved a big box-office success. But, to me, rating it as an important achievement is something like tossing a brick through a plate glass window and calling it “renovation”. The brick-tossing may qualify as a political statement. Perhaps even leading to the installation of a better window. But there’s no inherent beauty in the act itself. “Blazing Saddles” may indeed have ushered in a climate where new freedoms could be used creatively and constructively. That I can just about concede. But, for me, the picture’s crude, poorly executed and unfunny. And its real legacy is more likely the long line of dumb-ass gross-out comedies that have slithered down the pike in the years since. Having said that, let me hasten to add that from all aspersions cast on “Blazing Saddles”, I hold Madeline Kahn totally exempt. By dint of her own unique and considerable genius, she consistently rises above the drek.

I find a natural resistance rising within me when I see “Blazing Saddles” referred to as an important achievement. I guess it’s because that kind of implies a substantial amount of artistic merit. The picture DID thumb its nose at a lot of longstanding taboos – and proved a big box-office success. But, to me, rating it as an important achievement is something like tossing a brick through a plate glass window and calling it “renovation”. The brick-tossing may qualify as a political statement. Perhaps even leading to the installation of a better window. But there’s no inherent beauty in the act itself. “Blazing Saddles” may indeed have ushered in a climate where new freedoms could be used creatively and constructively. That I can just about concede. But, for me, the picture’s crude, poorly executed and unfunny. And its real legacy is more likely the long line of dumb-ass gross-out comedies that have slithered down the pike in the years since. Having said that, let me hasten to add that from all aspersions cast on “Blazing Saddles”, I hold Madeline Kahn totally exempt. By dint of her own unique and considerable genius, she consistently rises above the drek. Later that year she added significantly to her laurels in Mel Brooks’ amazing, “Young Frankenstein”. Here, virtually all the elements clicked magically into place. And Kahn’s own brilliance was reflected right back at her from every facet of the production. The picture’s visuals have been widely – and deservedly – praised over the years. Astonishingly evocative sets, eloquent camerawork, witty editing – and of course, the brilliant decision to go with black and white. John Morris, responsible for the flat-footed music in “Blazing Saddles”, here offers a score that originally may have been intended as affectionate over-the-top parody but is actually overtaken by its own genuine loveliness. A case similar to the genesis of Cole Porter’s song “Wunderbar” (from “Kiss Me Kate”), conceived as a satire of schmaltzy operetta waltzes but suffused with so much stand-alone beauty, it’s become a classic.

Later that year she added significantly to her laurels in Mel Brooks’ amazing, “Young Frankenstein”. Here, virtually all the elements clicked magically into place. And Kahn’s own brilliance was reflected right back at her from every facet of the production. The picture’s visuals have been widely – and deservedly – praised over the years. Astonishingly evocative sets, eloquent camerawork, witty editing – and of course, the brilliant decision to go with black and white. John Morris, responsible for the flat-footed music in “Blazing Saddles”, here offers a score that originally may have been intended as affectionate over-the-top parody but is actually overtaken by its own genuine loveliness. A case similar to the genesis of Cole Porter’s song “Wunderbar” (from “Kiss Me Kate”), conceived as a satire of schmaltzy operetta waltzes but suffused with so much stand-alone beauty, it’s become a classic.The sheer provocative power of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel has stood the test of time. I’ve studied it in two separate university literature courses over the years – and both times this was the book that prompted the most animated , prolonged and passionate in-class discussion. There’s something elemental here – and Brooks and Wilder found a way to put a comic spin on it while still preserving just enough of the story’s melancholy majesty. Their script is diamond-sharp. Rich and thoughtful. But gut-bustingly funny too. The success ratio of the gags in the picture is really pretty astounding.

The cast, of course, is classic. Gene Wilder’s quirky, endearing presence is a perfect fit, Teri Garr’s the flakiest of strudels (“Put … the …candle … back.”). Cloris Leachman makes domestic gorgon Frau Blucher the centrepiece of a surprisingly hilarious running gag about terrified horses. And of all the actors who’ve played the Frankenstein monster in the movies, only Karloff surpasses Peter Boyle. What happened to HIS nomination? Even a couple of non-castings add to the picture’s overall quality. Thank goodness Brooks regular Harvey Korman didn’t get his hands on the Lionel Atwill role. He’d have mangled it. I’m no great fan of Kenneth Mars. But he rises to the occasion with some very funny line readings:

“A riot ees an ugly theeng – unt I theenk eet ees jest about time ve hed vun.”

Not to mention his deft manipulations of the Hand. And somehow Mel Brooks resisted the temptation of grabbing a role for himself. As it is, the Borscht Belt schtick bubbles along at just the right pace.. And putting Brooks, with his inherently pushy, abrasive onscreen persona, into the mix might possibly have gummed things up a bit. But he wisely concentrated all his energies off-camera – and to tremendous effect. “Young Frankenstein”’s his masterpiece.

Which brings us to Madeline Kahn’s Elizabeth, one of cinema’s perfect creations. No matter what scene she’s in, no matter which moment you catch, she’s mind-blowing. Ridiculous. Sexy. Ridiculously sexy. We see her first at the train station, swathed in furs. Playing an epic goodbye scene as if she’s on a teeter-totter. She doesn’t just march to her own drummer. There’s a whole roof-garden dance band playing in her head – to alternating rhythms of “come and get me” and “touch-me-not”. A smorgasbord of conflicting signals. And even with “Keep off” signs flashing all over her (“hair … lips … nails …taffeta”), she’s constantly promising earthly delights, constantly saving herself – this particular time for “that party at Nana and Nicky’s”.

Which brings us to Madeline Kahn’s Elizabeth, one of cinema’s perfect creations. No matter what scene she’s in, no matter which moment you catch, she’s mind-blowing. Ridiculous. Sexy. Ridiculously sexy. We see her first at the train station, swathed in furs. Playing an epic goodbye scene as if she’s on a teeter-totter. She doesn’t just march to her own drummer. There’s a whole roof-garden dance band playing in her head – to alternating rhythms of “come and get me” and “touch-me-not”. A smorgasbord of conflicting signals. And even with “Keep off” signs flashing all over her (“hair … lips … nails …taffeta”), she’s constantly promising earthly delights, constantly saving herself – this particular time for “that party at Nana and Nicky’s”. When she shows up at the castle – Peggy Lee profile and white turban – she launches into a little comic chamber music with Wilder, Garr and Feldman. She coos. She vibrates But at any given moment, it’s quite impossible to tell whether she’s a cello, a theramin or a didgeridoo. What IS undeniable though is the electric charge running between her and her three colleagues. It’s Frankenstein’s lab all over again - with every mechanized pinwheel spinning and crackling. The bedroom scene with Wilder displays her come hither/don’t try it routine in full glory. She even makes baby talk work. And who else can do that?

When she shows up at the castle – Peggy Lee profile and white turban – she launches into a little comic chamber music with Wilder, Garr and Feldman. She coos. She vibrates But at any given moment, it’s quite impossible to tell whether she’s a cello, a theramin or a didgeridoo. What IS undeniable though is the electric charge running between her and her three colleagues. It’s Frankenstein’s lab all over again - with every mechanized pinwheel spinning and crackling. The bedroom scene with Wilder displays her come hither/don’t try it routine in full glory. She even makes baby talk work. And who else can do that? Of course, once she’s had the Elsa Lanchester make-over, she takes us on a really wild ride. Her eyes have definitely seen the glory – not to mention her hair. The post-coital cigarette, the “you men are all alike” tirade. And the honeymoon. Still with the baby talk. But now there’s a side-order of hissing steam heat to go with it. How on earth do you pick a favorite Kahn moment in this film?

Of course, once she’s had the Elsa Lanchester make-over, she takes us on a really wild ride. Her eyes have definitely seen the glory – not to mention her hair. The post-coital cigarette, the “you men are all alike” tirade. And the honeymoon. Still with the baby talk. But now there’s a side-order of hissing steam heat to go with it. How on earth do you pick a favorite Kahn moment in this film?“Would you want me like this – now - so soon before our wedding – so near we can almost touch it?”

Yes, Madeline, we want you now.

Monday, November 06, 2006

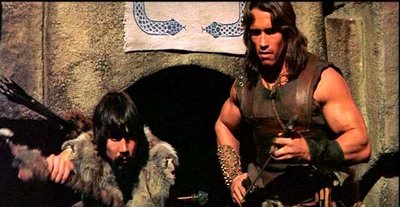

1982: The Overlooked -- SANDAHL BERGMAN in Conan the Barbarian

I love swashbucklers. Knights, highwaymen, pirates, desert warriors and Vikings too. So I was right on board with the mini-boom of sword and sorcery films that popped up in the early 80’s. The cycle petered out quickly. But it sowed the seeds that sprouted up a decade or so later with Xena. And let’s face it. This kind of picture’s never really going to disappear. There’s just too much potential for exotic fun, high adventure and sweeping spectacle. Sometimes the women in these films function on a purely decorative level. But the genre’s been known to accommodate some feisty, full-blooded heroines, too. Maureen O’Hara could parry and thrust with the best of them. And Lucy Lawless put some serious spark in the Dark Ages. But I think the warrior maiden I’m fondest of would have to be the marvelous Sandahl Bergman. She had the good fortune to appear in the best of the sword and sorcery films, “Conan the Barbarian”. But I’d say her participation in the picture is one of the reasons it IS the best.

I love swashbucklers. Knights, highwaymen, pirates, desert warriors and Vikings too. So I was right on board with the mini-boom of sword and sorcery films that popped up in the early 80’s. The cycle petered out quickly. But it sowed the seeds that sprouted up a decade or so later with Xena. And let’s face it. This kind of picture’s never really going to disappear. There’s just too much potential for exotic fun, high adventure and sweeping spectacle. Sometimes the women in these films function on a purely decorative level. But the genre’s been known to accommodate some feisty, full-blooded heroines, too. Maureen O’Hara could parry and thrust with the best of them. And Lucy Lawless put some serious spark in the Dark Ages. But I think the warrior maiden I’m fondest of would have to be the marvelous Sandahl Bergman. She had the good fortune to appear in the best of the sword and sorcery films, “Conan the Barbarian”. But I’d say her participation in the picture is one of the reasons it IS the best. “Conan” had a lot of other things going for it, too. A substantial budget, for instance. When moneybags Dino De Laurentiis came on board as executive producer, it was clear “Conan” would be travelling first-class. The script (co-written by Oliver Stone, no less) embellished its central quest with imaginative details and picaresque digressions. But it still sustained its forward momentum. There was plenty of scope for action but the narrative passages in between were nicely judged – frequently riding a wave of pulp poetry. John Milius turned out to be an ideal director for the piece, energetic and meticulous. He planned and guided the project like a giant military campaign, communicating his own enthusiasm to colleagues at every level.

“Conan” had a lot of other things going for it, too. A substantial budget, for instance. When moneybags Dino De Laurentiis came on board as executive producer, it was clear “Conan” would be travelling first-class. The script (co-written by Oliver Stone, no less) embellished its central quest with imaginative details and picaresque digressions. But it still sustained its forward momentum. There was plenty of scope for action but the narrative passages in between were nicely judged – frequently riding a wave of pulp poetry. John Milius turned out to be an ideal director for the piece, energetic and meticulous. He planned and guided the project like a giant military campaign, communicating his own enthusiasm to colleagues at every level.I would have bet money that Arnold Schwarzenegger would never make it as a film star.

Certainly, in most kinds of swashbucklers, he couldn’t have pulled it off. He’s no Don Juan or Scaramouche. Brocades, plumed hats and courtly speeches are definitely not in his comfort zone. But the role of Conan required a more Cro-Magnon approach. Brute strength and grunting determination were the order of the day. And for these things, Schwarzenegger’s a good fit. Even those thick-eared speech patterns that mark him as something of a Teutonic hillbilly were not inappropriate. Conan doesn’t have that much dialogue anyway. And seeing as the script has him brutalized into a kind of stoic silence during his formative years, it makes sense that, conversationally, he’s a late bloomer. Flowery speeches needn’t come trippingly to the tongue. The role called for neither the pretty nor the prolix. It did, however, demand commitment. Something Schwarzenegger was ready, willing and able to provide.

Certainly, in most kinds of swashbucklers, he couldn’t have pulled it off. He’s no Don Juan or Scaramouche. Brocades, plumed hats and courtly speeches are definitely not in his comfort zone. But the role of Conan required a more Cro-Magnon approach. Brute strength and grunting determination were the order of the day. And for these things, Schwarzenegger’s a good fit. Even those thick-eared speech patterns that mark him as something of a Teutonic hillbilly were not inappropriate. Conan doesn’t have that much dialogue anyway. And seeing as the script has him brutalized into a kind of stoic silence during his formative years, it makes sense that, conversationally, he’s a late bloomer. Flowery speeches needn’t come trippingly to the tongue. The role called for neither the pretty nor the prolix. It did, however, demand commitment. Something Schwarzenegger was ready, willing and able to provide.An awesome work ethic had helped propel him to the top of the body-building world. And he brought the same dedication and focus to his work in “Conan”. He’s really good with the heavy archaic weapons and props, achieving a kind of resolute fluidity one would never have thought possible in him. Schwarzenegger was not a man to be underestimated. He knew how to keep his eye on the prize, an ability that eventually led him to success in some pretty unexpected real-life arenas.

As far as his film career goes, it was the success of “Conan” that gave him movie star credibility with the public. And provided him entrée into other big-budget assignments. “Terminator”, “Total Recall”, “True Lies” – these all came later. But it’s “Conan” that got the juggernaut rolling.

Secondary casting in the film’s effective too. The picture opens explosively with the ambush that destroys Conan’s village and uproots him. The boy wordlessly playing young Conan is no stick figure. He’s expressive and affecting. The actors portraying his parents have only the briefest of opportunities to make an impact. But they concentrate so much charisma, character and intensity into those fleeting moments that their deaths are genuinely wrenching. Max Von Sydow brings a plummy authority to his single scene as a cantankerous king, hamming it up in all the right ways. The over-familiar James Earl Jones, villain of the piece, is given a look so striking – long straight hair and icy blue contacts, nicely augmented with some quirky reptilian moves of his own – that never once do the words “Verizon Wireless” cross your mind.

Terrific and unusual locations combine with spectacular art direction to create a massively believable fantasy world. Check out the pervasive twining motifs adorning the snake cult temples. Not since Alessandro Blasetti’s wild 1941 masterpiece “La Corona di Ferro” had so many mythic visual/cultural elements been mixed into such a dizzy and satisfying swirl. The physical solidity of the whole production reverberates with the ringing clang of hammer on anvil. That’s reflected in Basil Poledouris’ rousing neo-barbaric score, too. All resounding brass and thundering timpani. He occasionally borrows from the choral style of “Carmina Burana” – totally appropriate here. Elsewhere he daubs the landcape with a mix of primal colors and elegant pastels. Enriching and enhancing an already heady experience.

Conan’s adventurous arc gets underway quickly. Forty minutes in, it’s already clear the film’s a winner. Then everything’s kicked up a notch. Because that’s when Sandahl Bergman gets swept into the story. Conan and a sidekick have embarked on a recklessly under-strategized night-time assault on one of the snake cult’s crazy temple/towers. The goals – vengeance, theft of a fabulous jewel and maybe just a little general hell-raising. That’s when they run smack dab into solo brigand Valeria (Bergman) who’s apparently staging her own larcenous attack on the tower. She emerges from behind a pillar. A striking presence. Alert. Lithe. A blonde beauty – but no pampered princess or runway cutie. Bergman’s background was in dance (She’d turned a few heads with a flashy solo in Bob Fosse’s “All That Jazz” a couple of years before). And she sizzles with energy and cat-like grace. Her face has a frank, gutsy beauty – straight planes, an almost Quaker-ish simplicity. But the eyes are vigilant … searching. There’s a bruised, lived-in quality in her. She’s someone who’s emerged from experience like tempered steel. Robust, self-reliant, down-to-earth. So many impressions are conveyed – yet, at bottom, she’s a mystery woman. The credits identify her as Valeria but her name’s never actually spoken onscreen. Her origins, her backstory remain shrouded. Still, there’s no doubt that, like Conan, there’s derring-do in her past. And that, like him, she’s the pilot of her own destiny. Now, suddenly – fully engaged in rival robbery operations – the two come face to face.

Conan’s adventurous arc gets underway quickly. Forty minutes in, it’s already clear the film’s a winner. Then everything’s kicked up a notch. Because that’s when Sandahl Bergman gets swept into the story. Conan and a sidekick have embarked on a recklessly under-strategized night-time assault on one of the snake cult’s crazy temple/towers. The goals – vengeance, theft of a fabulous jewel and maybe just a little general hell-raising. That’s when they run smack dab into solo brigand Valeria (Bergman) who’s apparently staging her own larcenous attack on the tower. She emerges from behind a pillar. A striking presence. Alert. Lithe. A blonde beauty – but no pampered princess or runway cutie. Bergman’s background was in dance (She’d turned a few heads with a flashy solo in Bob Fosse’s “All That Jazz” a couple of years before). And she sizzles with energy and cat-like grace. Her face has a frank, gutsy beauty – straight planes, an almost Quaker-ish simplicity. But the eyes are vigilant … searching. There’s a bruised, lived-in quality in her. She’s someone who’s emerged from experience like tempered steel. Robust, self-reliant, down-to-earth. So many impressions are conveyed – yet, at bottom, she’s a mystery woman. The credits identify her as Valeria but her name’s never actually spoken onscreen. Her origins, her backstory remain shrouded. Still, there’s no doubt that, like Conan, there’s derring-do in her past. And that, like him, she’s the pilot of her own destiny. Now, suddenly – fully engaged in rival robbery operations – the two come face to face.Decisions have to be taken instantaneously on both sides. Pros and cons are weighed in a heartbeat. Valeria’s actually a little better equipped for the caper. She knows about the inner workings of the tower. Conan can profit from her knowledge. She can use the extra brawn. Without actually articulating it, they join forces. Swiftness is all-important – and Valeria’s participation proves essential in pulling off the heist. Like Schwarzenegger, Bergman had obviously committed to the fight training. But her aptitude’s even greater than his. It’s one of the film’s joys to see her grace and urgency of movement applied to some really breathtaking fight choreography and swordsmanship.

Once inside, they overcome a horde of bad guys, battle a spectacular (non CG) giant snake and snatch the jewel. The whole sequence rattles along with crackling panache. They’re off – with the enraged snake cultists in hot pursuit. And now they’re a team. A montage – and now they’re lovers. And, what do you know, it’s convincing. The movie really does capture the exhilarating feeling of lives led separately. colliding suddenly in the night and changing forever. There’s scarcely time to breathe and the adventure hurtles on. But now there’s a new equation – constellations have re-aligned, the earth’s axis has shifted.

Longtime loner Valeria makes a big decision, lets down her guard and decides to tell Conan she’s ready for commitment. This is the moment when Bergman consolidates her claim to screen glory – in a beautiful heartfelt speech. No Actors’ Studio veteran could invest the words with more intensity or sincerity than Bergman does in her stripped-down, emotional delivery. It’s to the bone.

Longtime loner Valeria makes a big decision, lets down her guard and decides to tell Conan she’s ready for commitment. This is the moment when Bergman consolidates her claim to screen glory – in a beautiful heartfelt speech. No Actors’ Studio veteran could invest the words with more intensity or sincerity than Bergman does in her stripped-down, emotional delivery. It’s to the bone.“I have never had so much as now.

All my life I’ve been alone.

Many times I’ve faced my death with no one to know.

I would look into the huts and the tents of others in the coldest dark.

And I would see figures holding each other in the night.

But I always passed by.

You and I have warmth.

That’s so hard to find in this world.

Please let someone else pass by in the night.”

All my life I’ve been alone.

Many times I’ve faced my death with no one to know.

I would look into the huts and the tents of others in the coldest dark.

And I would see figures holding each other in the night.

But I always passed by.

You and I have warmth.

That’s so hard to find in this world.

Please let someone else pass by in the night.”

Conan, obsessively dedicated to his quest and reluctant to put Valeria in danger, slips away in the night, leaving her behind. Bergman’s out of the picture for a long stretch now, that absence underlining her status as a supporting rather than leading player in the film. But just as Conan’s about to expire from an especially imaginative crucifixion, she returns in the nick of time to save him. And you can imagine a theatre full of kids erupting with thunderous hoots and hollers. The cavalry’s arrived! She literally wills him back to life with a pledge to the gods that seals her own fate.

She builds on the effect of her previous speech with another one, so embedded in her role that every line sounds as if her life depends on it.

“If I were dead and you were still fighting for life

I’d come back from the darkness

Back from the pit of Hell

And fight by your side.”

I’d come back from the darkness

Back from the pit of Hell

And fight by your side.”

Valeria dies – and Conan tends her funeral pyre. But return she does – in spectral form and shining armour – to save him one more time. In the end, Conan walks ambiguously into the sunset with a sexy princess, her rescue a side-effect of his adventurous quest. But it’s clear she could never be more than a consolation prize next to Valeria, the stalwart, shining (yet utterly real) Superwoman embodied by Sandahl Bergman.

Valeria dies – and Conan tends her funeral pyre. But return she does – in spectral form and shining armour – to save him one more time. In the end, Conan walks ambiguously into the sunset with a sexy princess, her rescue a side-effect of his adventurous quest. But it’s clear she could never be more than a consolation prize next to Valeria, the stalwart, shining (yet utterly real) Superwoman embodied by Sandahl Bergman.This memorable appearance seemed to forecast a long and interesting career to come. For whatever reasons, it never materialized. I remember excitedly setting out to see her in a 1982 version of Rider Haggard’s “She”. I’d always loved the book – movies had never done right by it. And of course I was sky-high on Bergman, post-Conan.. What a disappointment! A tattered quickie that chose to relocate the story to a post-apocalyptic (i.e. no budget) setting, then just kept the camera rolling, untended. It came across like one of those reality show challenges (“You have $500 and 48 hours to make a full-length adventure movie in the city dump. Your time starts now.”). It’s a set-up that would have defeated the combined resources of the entire Redgrave family. In the circumstances, all Bergman could do was grit her teeth and get through it. A couple of years later she turned up in the “Conan”-ish “Red Sonja”. It at least represented a return to mainstream moviemaking. Purportedly, Bergman turned down the title role, choosing instead to play the villainess. It may have seemed a good decision on paper. But the results were less than gratifying. Arnold Schwarzenegger seemed under-invested in his role, probably recognizing it correctly as not a milestone – but a minor hiccup – in his march to success. The talents of leading lady Brigitte Nielsen began and ended with swordplay. And she soon settled for brief tabloid notoriety and, eventually, a particularly tacky residence on “The Surreal Life”.

As for Bergman (brunette this time out), she lacked the villainous flair of, say, Faye Dunaway. The clearwater tones she’d used to project Valeria’s forthrightness seemed inappropriate. The wicked queen needed deeper, more insidious bottom notes and a much more theatrical flourish.

Perhaps Bergman had simply made too indelible an impression as the heroic Valeria to ever truly convince as a bad apple. Some action fans say she’s good in “Hell Comes to Frogtown” with wrestler Roddy Piper. The title’s always been enough to keep me away. But, then, I wasn’t aware till recently that Bergman was even in it. So. you know, I may investigate it – just to spend a little more time with her.

Perhaps Bergman had simply made too indelible an impression as the heroic Valeria to ever truly convince as a bad apple. Some action fans say she’s good in “Hell Comes to Frogtown” with wrestler Roddy Piper. The title’s always been enough to keep me away. But, then, I wasn’t aware till recently that Bergman was even in it. So. you know, I may investigate it – just to spend a little more time with her.Academy members had their noses in the air when they ignored Bergman’s Valeria at nomination time. But in my own personal alternate universe, she stands as one of the great fantasy film creations – superb role model, fierce fighter, the loyal friend we’d all love to have watching our backs and – no doubt about it – one of the five supporting actress nominees of 1982.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

1982: The Overlooked -- LAINIE KAZAN in My Favorite Year

LAINIE KAZAN in My Favorite Year

When Barbra Streisand exploded into prominence in the early 60’s, the entertainment world had never seen anything quite like her. Record companies scrambled to find cookie-cutter clones. In the end, what they unearthed was a number of young female singers – some gifted, some not so much – who operated in the same general show tune/cabaret ballpark. Commercially, none of them really ever hit it out of that park. Streisand’s staggering once-in-a-generation success wasn’t an act anyone was likely to duplicate. But some of them produced fine recordings and built nice little careers for themselves. Names like Lana Cantrell, Marilyn Michaels and Bobbe Norris twinkle honorably in the outer reaches of the 60’s firmament. With the exception of the talented Roslyn Kind (who actually WAS Streisand’s half-sister), none of these ladies stood quite so squarely in Barbra’s shadow as Lainie Kazan. She understudied her in Broadway’s Funny Girl. Who knows how many times she actually went on for the star? But it’s safe to say it would have been some scary mission to win over a packed house of Streisand-hungry paying customers who’d just been told their idol wouldn’t be appearing that night. If anyone was equipped to pull it off it was Kazan. Judging from the marvelous singing voice evident on her LP’s and the enormous comic talent she later revealed onscreen, it seems likely she would have made one hell of a Fannie Brice.

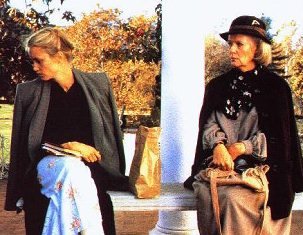

When Barbra Streisand exploded into prominence in the early 60’s, the entertainment world had never seen anything quite like her. Record companies scrambled to find cookie-cutter clones. In the end, what they unearthed was a number of young female singers – some gifted, some not so much – who operated in the same general show tune/cabaret ballpark. Commercially, none of them really ever hit it out of that park. Streisand’s staggering once-in-a-generation success wasn’t an act anyone was likely to duplicate. But some of them produced fine recordings and built nice little careers for themselves. Names like Lana Cantrell, Marilyn Michaels and Bobbe Norris twinkle honorably in the outer reaches of the 60’s firmament. With the exception of the talented Roslyn Kind (who actually WAS Streisand’s half-sister), none of these ladies stood quite so squarely in Barbra’s shadow as Lainie Kazan. She understudied her in Broadway’s Funny Girl. Who knows how many times she actually went on for the star? But it’s safe to say it would have been some scary mission to win over a packed house of Streisand-hungry paying customers who’d just been told their idol wouldn’t be appearing that night. If anyone was equipped to pull it off it was Kazan. Judging from the marvelous singing voice evident on her LP’s and the enormous comic talent she later revealed onscreen, it seems likely she would have made one hell of a Fannie Brice. Kazan's bigscreen credits in the 60’s and 70’s were negligible. But a solid gold opportunity finally came her way when she was offered the role of Belle in My Favorite Year. It’s the part that became her calling card. The picture itself was the year’s most engaging sleeper, merrily immersing audiences in the backstage chaos of a 1954 TV variety show. Constructed around a sharp, funny, observant screenplay, it radiated nostalgic charm. Even the title was adroitly chosen. It’s a nice idea having a favorite year. Makes you pause and think about what your own might be. A sweet concept – and one that pulls you into the film from the get-go.

Kazan's bigscreen credits in the 60’s and 70’s were negligible. But a solid gold opportunity finally came her way when she was offered the role of Belle in My Favorite Year. It’s the part that became her calling card. The picture itself was the year’s most engaging sleeper, merrily immersing audiences in the backstage chaos of a 1954 TV variety show. Constructed around a sharp, funny, observant screenplay, it radiated nostalgic charm. Even the title was adroitly chosen. It’s a nice idea having a favorite year. Makes you pause and think about what your own might be. A sweet concept – and one that pulls you into the film from the get-go.Major credit’s due to director Richard Benjamin, who made a series of very wise choices. One of which was the brilliant use of Nat Cole’s thrilling version of “Stardust” to open the picture. The arrangement’s achingly beautiful, priming us for an experience that uses comedy as an integral part of something warmer and richer.

But it was in the casting that Benjamin really hit 24 karat paydirt. Peter O’Toole was a pluperfect fit as Allan Swann, the ruefully boisterous, disaster-prone and ultimately endearing swashbuckler, Mark Linn-Baker, a terrific new discovery as Benjy, the junior writer assigned to bring him back alive –and sober. Joseph Bologna is beyond wonderful – way beyond – as King Kaiser, a Sid Caesar style TV star. Wrapped in a sort of cagey befuddlement, dispatching insanely inappropriate gifts to his staff and – in the end – game for anything. It’s a brilliant, one-of-a-kind creation. Caesar himself couldn’t have hoped for a warmer, funnier tribute. And it’s absolutely unfawning. [Aside from Bologna, the field of potential supporting actor candidates in ’82 was astonishing – Mickey Rourke(Diner), Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner) , Jack Warden (The Verdict). Amazingly, not one of them was even nominated. But I’d say they could have mass-produced the trophy that year and given each of these guys one of his own.] My Favorite Year also spotlights uproarious turns from veteran Cameron Mitchell, a grimly funny gangster and frog-in-her-throat wardrobe lady Selma Diamond. Plus a lovely bit from 30’s star and future Titanic icon Gloria Stuart.

Even in this illustrious company, Lainie Kazan stood out. And not just because she was 5’11”. Kazan plays Belle, Benjy’s flamboyant Brooklyn mother and she plays her to the hilt. It takes an actor who’s both brave and gifted to pull off a broad stroke performance. Over-the-top efforts by lesser lights are inevitably embarrassments. If you don’t have the helium to begin with, the balloon’s still gonna be enormous but it ain’t ever gonna fly. Belle embodies one of cinema’s archetypes – the Jewish mother. Alarmingly loving, overbearing, regally tacky and armed with an endless supply of straight-faced sour pickle one-liners worthy of a Borscht Belt headliner. Of course, there’s also the usual to-do list for her son, either explicitly stated or strongly implied:

Even in this illustrious company, Lainie Kazan stood out. And not just because she was 5’11”. Kazan plays Belle, Benjy’s flamboyant Brooklyn mother and she plays her to the hilt. It takes an actor who’s both brave and gifted to pull off a broad stroke performance. Over-the-top efforts by lesser lights are inevitably embarrassments. If you don’t have the helium to begin with, the balloon’s still gonna be enormous but it ain’t ever gonna fly. Belle embodies one of cinema’s archetypes – the Jewish mother. Alarmingly loving, overbearing, regally tacky and armed with an endless supply of straight-faced sour pickle one-liners worthy of a Borscht Belt headliner. Of course, there’s also the usual to-do list for her son, either explicitly stated or strongly implied:He should be a doctor or a lawyer.

He should marry a nice Jewish girl.

He should EAT! EAT!

For me, it’s a stereotype with plenty of mileage left in it. Unlike, say, the bimbo chorine of Victor/Victoria. Getting laughs out of that one is like trying to squeeze them out of a Brillo pad. Chances of extracting honest-to-goodness sentiment from it are even slimmer. But it’s different with a Jewish mother. The possibilities for hitting a chord are there in spades. After all, Jewish or not, most of us have done a lot more interacting with mothers than with chorus girls.

Whatever the case, Kazan surveys the territory, decides there’s gold in them thar hills and proceeds to mine it with pick, shovel, dynamite and a little seltzer. She’s Hurricane Belle, bulldozing Benjy into hauling celebrity Swann out to her Brooklyn lair for a family dinner. The potential for a disastrous collision of incongruities never enters her mind. Because, when all’s said and done, Belle’s proud of herself and her brood. And sees no reason why Swann shouldn’t take a shine to them too.

She and Benjy operate not just as mother and son, but as a well-oiled comedy duo, too, with Mom the inevitable top banana. Kazan’s Belle emerges with door-filling grandeur, the hostess gown she’s stuffed into a compelling argument against the theory that black is slimming. But that just qualifies her all the more to preside over the dinner party. It’s her big showpiece.

She’s clearly proud of her Benjy. But that doesn’t stop her from swatting away his opinions and asides, treating them like heckling mosquitos at a Catskills picnic.

Belle: “Welcome to my little chapeau”

Benjy: “Two years at the Sorbonne and she still can’t get that one right.”

Her kingdom’s a matriarchy and she sends out maternal rays that entangle the evening like the arms of an amiable octopus. O’Toole’s Swann recognizes her for what she is. Exasperatingly loveable. With no hidden agenda. Belle’s agendas are all spread out on the table like a gargantuan canasta hand. “Swanee”, she calls him, leaning in with conspiratorial splendor to ladle out advice. By the end of the dinner party, she’s taken the whole movie on a sidetrip to another galaxy. And when Swann leaves the building, he’s more or less carried along by the whole delightfully preposterous population of Planet Belle.

It’s worth pointing out that’82 saw Kazan adding further luster to her reputation as a dynamic new comic talent. And she managed to do it in one of the year’s ultra-bombs, Coppola’s epic miscalculation One From the Heart. She’s heroine Teri Garr’s best friend – and the one and only source of fun in the whole weary soundstage wasteland. Kazan plays Maggie, plus-size travel agent/cocktail waitress - forever handing out common-sense advice, none of which she’s able to apply to her own shambles of a social life.

The picture’s art-directed to extinction. And suffocates under the weight of Tom Waits’ gloomy songs, which course turgidly through the film like embalming fluid. I mean, imagine putting Lainie Kazan into a musical film and then not letting her sing!. As a musical, the film only works during a brief, silhouetted tango - tightly choreographed and expertly danced by Garr and Raul Julia. A big, misbegotten production number on the "streets” of Las Vegas is an all-out embarrassment – like a conga line breaking out at a funeral.

But bobbing in and out of the picture – all too infrequently – Kazan somehow dodges the stun-gun pellets that level everyone around her. Whether hysterically heading out at 3 a.m. to meet some bum, or extending an eloquent arm from her door to reel in consolation prize Harry Dean Stanton, she’s a keeper.

But it’s Belle in My Favorite Year that gave Lainie Kazan her definitive showcase. And it’s the Kazan performance that was widely seen in ’82. People still nod fondly when it’s mentioned. It’s become her signature role. She even reprised it in a Broadway musical version of the film some years later. How she eluded an Oscar nomination is anybody’s guess. But it’s a performance that's lived on. And I wouldn’t be a bit surprised to learn that 1982 stands as Lainie Kazan’s own favorite year.

Sunday, October 29, 2006

SUPPORTING ACTRESSES 1982 –SCATTERED THOUGHTS

StinkyLulu hosts a near traffic jam of eager opinion givers in the latest supporting actress smackdown. The ladies prompting all the hubbub:

TERI GARR in “Tootsie”

Dustin Hoffman is the center of the universe in “Tootsie” – and it’s a pretty hollow center. As Michael Dorsey, he operates with his usual flat-voiced fussiness. As Dorothy Michaels, he successfully lightens the voice, but then falls back on a half-assed Southern accent (the Joyce Compton syndrome I call it, based on the faulty assumption that any old rot is funny if it’s delivered in a Dixie dialect). Unable to approximate charm, he achieves only a humorless perkiness. Luckily, Hoffman has two fine actresses to support and bail him out in scene after scene. Teri Garr’s glorious work is probably the best of her career. And though the movie sometimes seems to undervalue her as much as Michael does Sandy, she never lets that get in her way. Granted, the script gives her some extra-fine dialogue:

Dustin Hoffman is the center of the universe in “Tootsie” – and it’s a pretty hollow center. As Michael Dorsey, he operates with his usual flat-voiced fussiness. As Dorothy Michaels, he successfully lightens the voice, but then falls back on a half-assed Southern accent (the Joyce Compton syndrome I call it, based on the faulty assumption that any old rot is funny if it’s delivered in a Dixie dialect). Unable to approximate charm, he achieves only a humorless perkiness. Luckily, Hoffman has two fine actresses to support and bail him out in scene after scene. Teri Garr’s glorious work is probably the best of her career. And though the movie sometimes seems to undervalue her as much as Michael does Sandy, she never lets that get in her way. Granted, the script gives her some extra-fine dialogue:

“Sorry, I shouldn’t have people over for dinner. They never show up.”

But it’s Garr’s prodigious blend of physical and vocal timing that brings out all the possibilities – comic and otherwise – in a character that’s smart enough to be cynical, nice enough to be generous and vulnerable enough to make you care. She’s also hysterically funny. As the years go by, most of “Tootsie” melts away from the memory. But not Teri Garr’s Sandy. She soldiers on, shouting apologetic defiance, juggling indignation and resignation, neither of which ever quite extinguish the glimmer of hope . And all from behind her own private – and permanent - eight-ball.

JESSICA LANGE in “Tootsie”

1982 was the year Jessica Lange made the leap from garden variety starlet to much admired actress. And her work in “Tootsie” is key. Audiences were genuinely startled at just how good she was. It went beyond the warmth and naturalness, unexpected and welcome as they were. Lange definitely had the confidence to take her time. And a talent so strong she could instinctively adjust the tempo of a scene, usually to the advantage of all concerned. Her gifts tumbled across the screen. Has there ever been an actress who looked more natural –or acted more persuasively – with a baby on her arm? A simple line of dialogue, exquisitely delivered, (“He thinks I’m still twelve”) speaks tender volumes about her relationship with dad Charles Durning. There’s a lovely dinner table scene at Durning’s farmhouse, where Lange’s newly-minted star-power is on radiant display. She’s absolutely believable as the source of light and beauty reflected in Hoffman’s face, the reflection itself enough to dazzle Durning. Kudos, by the way, to Durning and Sydney Pollack for canny, resourceful playing. But, in the end, it’s the two ladies - Garr and Lange – who carry “Tootsie” across the finish line with something approaching triumph.

1982 was the year Jessica Lange made the leap from garden variety starlet to much admired actress. And her work in “Tootsie” is key. Audiences were genuinely startled at just how good she was. It went beyond the warmth and naturalness, unexpected and welcome as they were. Lange definitely had the confidence to take her time. And a talent so strong she could instinctively adjust the tempo of a scene, usually to the advantage of all concerned. Her gifts tumbled across the screen. Has there ever been an actress who looked more natural –or acted more persuasively – with a baby on her arm? A simple line of dialogue, exquisitely delivered, (“He thinks I’m still twelve”) speaks tender volumes about her relationship with dad Charles Durning. There’s a lovely dinner table scene at Durning’s farmhouse, where Lange’s newly-minted star-power is on radiant display. She’s absolutely believable as the source of light and beauty reflected in Hoffman’s face, the reflection itself enough to dazzle Durning. Kudos, by the way, to Durning and Sydney Pollack for canny, resourceful playing. But, in the end, it’s the two ladies - Garr and Lange – who carry “Tootsie” across the finish line with something approaching triumph.

KIM STANLEY in “Frances”

When Jessica Lange followed “Tootsie” with her top-billed tour-de-force in “Frances”, there was just no denying that a new and major talent had arrived. It’s a slow-building performance. But, ultimately, heartbreaking. Some scenes – including the final one – are almost too sad to watch. The script lays much of the blame for Frances’ tragedy on her ambitious, unstable mother. It’s a showy role and, to play it, the producers lured an acting heavyweight back to the screen. Kim Stanley proves up to the challenge. Her Lillian is prisoner and victim of her own destructive behavior. But she’s also a corrosive influence on those around her. Bursts of happiness and bouts of anger are both laced with desperation and fear – unhinged and profoundly dangerous. It’s a creative and unpredictable performance, bubbling and frequently threatening to boil over. Lillian sees Frances as her last chance at fulfillment. And when the young woman checkmates her, she allots only a moment to defeat, then fast-forwards to revenge mode, implacably signing off on her daughter’s damnation.

When Jessica Lange followed “Tootsie” with her top-billed tour-de-force in “Frances”, there was just no denying that a new and major talent had arrived. It’s a slow-building performance. But, ultimately, heartbreaking. Some scenes – including the final one – are almost too sad to watch. The script lays much of the blame for Frances’ tragedy on her ambitious, unstable mother. It’s a showy role and, to play it, the producers lured an acting heavyweight back to the screen. Kim Stanley proves up to the challenge. Her Lillian is prisoner and victim of her own destructive behavior. But she’s also a corrosive influence on those around her. Bursts of happiness and bouts of anger are both laced with desperation and fear – unhinged and profoundly dangerous. It’s a creative and unpredictable performance, bubbling and frequently threatening to boil over. Lillian sees Frances as her last chance at fulfillment. And when the young woman checkmates her, she allots only a moment to defeat, then fast-forwards to revenge mode, implacably signing off on her daughter’s damnation.

LESLEY ANN WARREN in “Victor/Victoria”

The success of the moribund “Victor/Victoria” remains a mystery to me. It’s interminable, stuffy and self-congratulatory , with about as much genuine atmosphere as a “Get Smart” episode. And, oh yes, it’s also not funny. Most of Henry Mancini’s score is inappropriate, regurgitating the sound of his 60’s heyday, achieving nothing remotely evocative of the 20’s. The only exception is the song “Le Jazz Hot”, a tune that’s both catchy and period-friendly. In the context, I wouldn’t call it a show-stopper. The picture moves at such a deadening snail’s pace it’s as good as stopped already. But it does jolt the film to life for a couple of minutes. And Julie Andrews’ costume for the number is a knockout. Imagine how great Lesley Ann Warren would have looked in it. As it is, she’s saddled with playing Norma, crude, conniving Brooklynesque dumb blonde showgirl/tart. This is a stereotype that has to be refracted through a very distinctive prism to yield anything new or worthwhile. It’s Barbara Nichols territory – and perhaps only she can negotiate the terrain with honest, high-heeled, squawk-voiced perfection. Warren’s performance is utterly and hopelessly generic. Something that might have just about passed muster on a half-rehearsed TV skit. The fact that it emerged as an audience pleaser is a puzzlement, the Oscar nomination a major mind-boggler. At very least, it’s a misuse of Warren’s rich and varied talents. Had it worked, the part might have provided some small relief from the goings-on. As it is, it’s just another standard issue rack in “Victor/Victoria”‘s already fully-stocked torture chamber.

The success of the moribund “Victor/Victoria” remains a mystery to me. It’s interminable, stuffy and self-congratulatory , with about as much genuine atmosphere as a “Get Smart” episode. And, oh yes, it’s also not funny. Most of Henry Mancini’s score is inappropriate, regurgitating the sound of his 60’s heyday, achieving nothing remotely evocative of the 20’s. The only exception is the song “Le Jazz Hot”, a tune that’s both catchy and period-friendly. In the context, I wouldn’t call it a show-stopper. The picture moves at such a deadening snail’s pace it’s as good as stopped already. But it does jolt the film to life for a couple of minutes. And Julie Andrews’ costume for the number is a knockout. Imagine how great Lesley Ann Warren would have looked in it. As it is, she’s saddled with playing Norma, crude, conniving Brooklynesque dumb blonde showgirl/tart. This is a stereotype that has to be refracted through a very distinctive prism to yield anything new or worthwhile. It’s Barbara Nichols territory – and perhaps only she can negotiate the terrain with honest, high-heeled, squawk-voiced perfection. Warren’s performance is utterly and hopelessly generic. Something that might have just about passed muster on a half-rehearsed TV skit. The fact that it emerged as an audience pleaser is a puzzlement, the Oscar nomination a major mind-boggler. At very least, it’s a misuse of Warren’s rich and varied talents. Had it worked, the part might have provided some small relief from the goings-on. As it is, it’s just another standard issue rack in “Victor/Victoria”‘s already fully-stocked torture chamber.

For a really charming adaptation of the same source material, see the British film “First a Girl” (1935) with marvelous Jessie Matthews. Light, airy and endearing, it bounces where “Victor/Victoria” merely thuds.

GLENN CLOSE in “The World According to Garp”

When Glenn Close arrived on the scene, ferociously determined, frighteningly focused, it seemed pretty clear there’d be no getting rid of her without multiple Oscar nominations. The first of these inevitable nods came for “Garp”. She’s certainly formidable . Professional as Hell, too. But , for me, not that appealing or charismatic. Definitely not amusing Or even what I’d call interesting. She’s just there. And you know you’re expected to pay attention – strict attention.. Still, the adulation, Jenny inspires in “Garp” is easier to buy into than, say, the Dorothy Michaels mania in “Tootsie”. After all, Jenny’s is supposed to be based largely on a book she wrote. In “Tootsie” we’re asked to believe the whole country goes gaga over Dorothy’s appearance, attitude and acting. Considering what we see onscreen, that’s not easy to swallow.

When Glenn Close arrived on the scene, ferociously determined, frighteningly focused, it seemed pretty clear there’d be no getting rid of her without multiple Oscar nominations. The first of these inevitable nods came for “Garp”. She’s certainly formidable . Professional as Hell, too. But , for me, not that appealing or charismatic. Definitely not amusing Or even what I’d call interesting. She’s just there. And you know you’re expected to pay attention – strict attention.. Still, the adulation, Jenny inspires in “Garp” is easier to buy into than, say, the Dorothy Michaels mania in “Tootsie”. After all, Jenny’s is supposed to be based largely on a book she wrote. In “Tootsie” we’re asked to believe the whole country goes gaga over Dorothy’s appearance, attitude and acting. Considering what we see onscreen, that’s not easy to swallow.

Maybe I' ll just never get past seeing Glenn Close as scary. For me, it's the one note in her performances that tends to drown out all the others. So, outside of “Fatal Attraction”

( where she’s supposed to be that way), I can’t say I’ve ever surrendered to her spell. Annette Bening plays the same character in “Valmont” that Close plays in “Dangerous Liaisons” – and she’s better equipped for the job. A Bening bitch can still seem quite capable of fooling people into thinking she’s nice. She’s an Eve Harrington Margo Channing would hire in a heartbeat. Close is just too damn intimidating. One look at her and Margo would hoist the “Vacancy Filled” sign and head for the hills.

- GLENN CLOSE “The World According to Garp”

- TERI GARR “Tootsie”

- JESSICA LANGE “Tootsie

- KIM STANLEY “Frances”

- LESLEY ANN WARREN “Victor/Victoria”

• • • • •

TERI GARR in “Tootsie”

Dustin Hoffman is the center of the universe in “Tootsie” – and it’s a pretty hollow center. As Michael Dorsey, he operates with his usual flat-voiced fussiness. As Dorothy Michaels, he successfully lightens the voice, but then falls back on a half-assed Southern accent (the Joyce Compton syndrome I call it, based on the faulty assumption that any old rot is funny if it’s delivered in a Dixie dialect). Unable to approximate charm, he achieves only a humorless perkiness. Luckily, Hoffman has two fine actresses to support and bail him out in scene after scene. Teri Garr’s glorious work is probably the best of her career. And though the movie sometimes seems to undervalue her as much as Michael does Sandy, she never lets that get in her way. Granted, the script gives her some extra-fine dialogue:

Dustin Hoffman is the center of the universe in “Tootsie” – and it’s a pretty hollow center. As Michael Dorsey, he operates with his usual flat-voiced fussiness. As Dorothy Michaels, he successfully lightens the voice, but then falls back on a half-assed Southern accent (the Joyce Compton syndrome I call it, based on the faulty assumption that any old rot is funny if it’s delivered in a Dixie dialect). Unable to approximate charm, he achieves only a humorless perkiness. Luckily, Hoffman has two fine actresses to support and bail him out in scene after scene. Teri Garr’s glorious work is probably the best of her career. And though the movie sometimes seems to undervalue her as much as Michael does Sandy, she never lets that get in her way. Granted, the script gives her some extra-fine dialogue:“Sorry, I shouldn’t have people over for dinner. They never show up.”

But it’s Garr’s prodigious blend of physical and vocal timing that brings out all the possibilities – comic and otherwise – in a character that’s smart enough to be cynical, nice enough to be generous and vulnerable enough to make you care. She’s also hysterically funny. As the years go by, most of “Tootsie” melts away from the memory. But not Teri Garr’s Sandy. She soldiers on, shouting apologetic defiance, juggling indignation and resignation, neither of which ever quite extinguish the glimmer of hope . And all from behind her own private – and permanent - eight-ball.

• • • • •

JESSICA LANGE in “Tootsie”

1982 was the year Jessica Lange made the leap from garden variety starlet to much admired actress. And her work in “Tootsie” is key. Audiences were genuinely startled at just how good she was. It went beyond the warmth and naturalness, unexpected and welcome as they were. Lange definitely had the confidence to take her time. And a talent so strong she could instinctively adjust the tempo of a scene, usually to the advantage of all concerned. Her gifts tumbled across the screen. Has there ever been an actress who looked more natural –or acted more persuasively – with a baby on her arm? A simple line of dialogue, exquisitely delivered, (“He thinks I’m still twelve”) speaks tender volumes about her relationship with dad Charles Durning. There’s a lovely dinner table scene at Durning’s farmhouse, where Lange’s newly-minted star-power is on radiant display. She’s absolutely believable as the source of light and beauty reflected in Hoffman’s face, the reflection itself enough to dazzle Durning. Kudos, by the way, to Durning and Sydney Pollack for canny, resourceful playing. But, in the end, it’s the two ladies - Garr and Lange – who carry “Tootsie” across the finish line with something approaching triumph.

1982 was the year Jessica Lange made the leap from garden variety starlet to much admired actress. And her work in “Tootsie” is key. Audiences were genuinely startled at just how good she was. It went beyond the warmth and naturalness, unexpected and welcome as they were. Lange definitely had the confidence to take her time. And a talent so strong she could instinctively adjust the tempo of a scene, usually to the advantage of all concerned. Her gifts tumbled across the screen. Has there ever been an actress who looked more natural –or acted more persuasively – with a baby on her arm? A simple line of dialogue, exquisitely delivered, (“He thinks I’m still twelve”) speaks tender volumes about her relationship with dad Charles Durning. There’s a lovely dinner table scene at Durning’s farmhouse, where Lange’s newly-minted star-power is on radiant display. She’s absolutely believable as the source of light and beauty reflected in Hoffman’s face, the reflection itself enough to dazzle Durning. Kudos, by the way, to Durning and Sydney Pollack for canny, resourceful playing. But, in the end, it’s the two ladies - Garr and Lange – who carry “Tootsie” across the finish line with something approaching triumph.• • • • •

KIM STANLEY in “Frances”

When Jessica Lange followed “Tootsie” with her top-billed tour-de-force in “Frances”, there was just no denying that a new and major talent had arrived. It’s a slow-building performance. But, ultimately, heartbreaking. Some scenes – including the final one – are almost too sad to watch. The script lays much of the blame for Frances’ tragedy on her ambitious, unstable mother. It’s a showy role and, to play it, the producers lured an acting heavyweight back to the screen. Kim Stanley proves up to the challenge. Her Lillian is prisoner and victim of her own destructive behavior. But she’s also a corrosive influence on those around her. Bursts of happiness and bouts of anger are both laced with desperation and fear – unhinged and profoundly dangerous. It’s a creative and unpredictable performance, bubbling and frequently threatening to boil over. Lillian sees Frances as her last chance at fulfillment. And when the young woman checkmates her, she allots only a moment to defeat, then fast-forwards to revenge mode, implacably signing off on her daughter’s damnation.

When Jessica Lange followed “Tootsie” with her top-billed tour-de-force in “Frances”, there was just no denying that a new and major talent had arrived. It’s a slow-building performance. But, ultimately, heartbreaking. Some scenes – including the final one – are almost too sad to watch. The script lays much of the blame for Frances’ tragedy on her ambitious, unstable mother. It’s a showy role and, to play it, the producers lured an acting heavyweight back to the screen. Kim Stanley proves up to the challenge. Her Lillian is prisoner and victim of her own destructive behavior. But she’s also a corrosive influence on those around her. Bursts of happiness and bouts of anger are both laced with desperation and fear – unhinged and profoundly dangerous. It’s a creative and unpredictable performance, bubbling and frequently threatening to boil over. Lillian sees Frances as her last chance at fulfillment. And when the young woman checkmates her, she allots only a moment to defeat, then fast-forwards to revenge mode, implacably signing off on her daughter’s damnation.• • • • •

LESLEY ANN WARREN in “Victor/Victoria”

The success of the moribund “Victor/Victoria” remains a mystery to me. It’s interminable, stuffy and self-congratulatory , with about as much genuine atmosphere as a “Get Smart” episode. And, oh yes, it’s also not funny. Most of Henry Mancini’s score is inappropriate, regurgitating the sound of his 60’s heyday, achieving nothing remotely evocative of the 20’s. The only exception is the song “Le Jazz Hot”, a tune that’s both catchy and period-friendly. In the context, I wouldn’t call it a show-stopper. The picture moves at such a deadening snail’s pace it’s as good as stopped already. But it does jolt the film to life for a couple of minutes. And Julie Andrews’ costume for the number is a knockout. Imagine how great Lesley Ann Warren would have looked in it. As it is, she’s saddled with playing Norma, crude, conniving Brooklynesque dumb blonde showgirl/tart. This is a stereotype that has to be refracted through a very distinctive prism to yield anything new or worthwhile. It’s Barbara Nichols territory – and perhaps only she can negotiate the terrain with honest, high-heeled, squawk-voiced perfection. Warren’s performance is utterly and hopelessly generic. Something that might have just about passed muster on a half-rehearsed TV skit. The fact that it emerged as an audience pleaser is a puzzlement, the Oscar nomination a major mind-boggler. At very least, it’s a misuse of Warren’s rich and varied talents. Had it worked, the part might have provided some small relief from the goings-on. As it is, it’s just another standard issue rack in “Victor/Victoria”‘s already fully-stocked torture chamber.

The success of the moribund “Victor/Victoria” remains a mystery to me. It’s interminable, stuffy and self-congratulatory , with about as much genuine atmosphere as a “Get Smart” episode. And, oh yes, it’s also not funny. Most of Henry Mancini’s score is inappropriate, regurgitating the sound of his 60’s heyday, achieving nothing remotely evocative of the 20’s. The only exception is the song “Le Jazz Hot”, a tune that’s both catchy and period-friendly. In the context, I wouldn’t call it a show-stopper. The picture moves at such a deadening snail’s pace it’s as good as stopped already. But it does jolt the film to life for a couple of minutes. And Julie Andrews’ costume for the number is a knockout. Imagine how great Lesley Ann Warren would have looked in it. As it is, she’s saddled with playing Norma, crude, conniving Brooklynesque dumb blonde showgirl/tart. This is a stereotype that has to be refracted through a very distinctive prism to yield anything new or worthwhile. It’s Barbara Nichols territory – and perhaps only she can negotiate the terrain with honest, high-heeled, squawk-voiced perfection. Warren’s performance is utterly and hopelessly generic. Something that might have just about passed muster on a half-rehearsed TV skit. The fact that it emerged as an audience pleaser is a puzzlement, the Oscar nomination a major mind-boggler. At very least, it’s a misuse of Warren’s rich and varied talents. Had it worked, the part might have provided some small relief from the goings-on. As it is, it’s just another standard issue rack in “Victor/Victoria”‘s already fully-stocked torture chamber.For a really charming adaptation of the same source material, see the British film “First a Girl” (1935) with marvelous Jessie Matthews. Light, airy and endearing, it bounces where “Victor/Victoria” merely thuds.

• • • • •

GLENN CLOSE in “The World According to Garp”