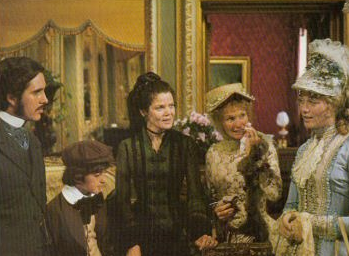

Had she been around then, Eileen Brennan’s expressive face – deep, dark eyes, opulent mouth, intoxicating sly-boots energy – might well have secured her stardom in silent films. Because she came later, we were lucky enough to hear her speak. As Mrs. Walker, elegant drawing-room piranha, she uses that voice to full effect. It’s pure India ink – rich, dark, luxurious, quite indelible. Her makeup is subdued but witchy, the total look suggesting a sort of gill-breathing Janis Paige. Unsettling, but just try to look away. She swims in an elite stream - an expert on every ripple in it. No stranger, one suspects, to its murkier depths. Certainly aware of its limits. And singularly displeased with anyone who openly swims against the current.

Had she been around then, Eileen Brennan’s expressive face – deep, dark eyes, opulent mouth, intoxicating sly-boots energy – might well have secured her stardom in silent films. Because she came later, we were lucky enough to hear her speak. As Mrs. Walker, elegant drawing-room piranha, she uses that voice to full effect. It’s pure India ink – rich, dark, luxurious, quite indelible. Her makeup is subdued but witchy, the total look suggesting a sort of gill-breathing Janis Paige. Unsettling, but just try to look away. She swims in an elite stream - an expert on every ripple in it. No stranger, one suspects, to its murkier depths. Certainly aware of its limits. And singularly displeased with anyone who openly swims against the current. Mrs. Walker is society to her fingertips. But, unlike Mrs. Costello, doesn’t feel totally secure in her position. Her status depends on a carefully constructed house of cards, not one of which must be removed or even jostled. Mrs. Costello’s closet may be skeleton-free. Mrs. Walker’s probably not. There are indications of a taste for illicit adventure. The near-constant presence of young blonde Nicholas Jones in her vicinity creates an impression, shall we say. One that tiptoes past the ambiguous into the neighborhood of the incriminating. She also casts a more than covetous eye on Mr. Winterbourne. Watch her speak to him. She seems to want to gobble him up. These appetites tend to jeopardize the delicate status quo. Mrs. Walker patrols the social scene, sensitive to the slightest seismic shift, knowing it could expose her foibles and put her at risk.

Mrs. Walker is society to her fingertips. But, unlike Mrs. Costello, doesn’t feel totally secure in her position. Her status depends on a carefully constructed house of cards, not one of which must be removed or even jostled. Mrs. Costello’s closet may be skeleton-free. Mrs. Walker’s probably not. There are indications of a taste for illicit adventure. The near-constant presence of young blonde Nicholas Jones in her vicinity creates an impression, shall we say. One that tiptoes past the ambiguous into the neighborhood of the incriminating. She also casts a more than covetous eye on Mr. Winterbourne. Watch her speak to him. She seems to want to gobble him up. These appetites tend to jeopardize the delicate status quo. Mrs. Walker patrols the social scene, sensitive to the slightest seismic shift, knowing it could expose her foibles and put her at risk.Daisy Miller presents a threat – on several levels – to Mrs. Walker’s peace of mind. She’s young and pretty. Check. Winterbourne’s evidently smitten. Double check. She’s also a wild card. Doesn’t play by the rules. Rocks the boat in unexpected ways. Triple check. Even Mrs. Walker’s smooth expertise as a hostess is jangled by Daisy’s pop-up non-sequiturs. Not to mention the willy-nilly antics of Daisy’s mother and brother. The whole family interferes with the rhythm of things – and the predictable rhythm of society is what Mrs. Walker depends on.

Brennan’s role climaxes with the carriage scene. Ostensibly, she’s out to save Daisy from compromising herself. In fact, she’s in hot pursuit of Winterbourne, propelled, in part, by that urge that makes us want to actually witness the thing that’s most galling to us. And of course, she means to stop Daisy - come Hell or high water – from once more rocking the boat. But Daisy’s pert-mouthed indifference, coupled with Winterbourne’s obvious infatuation, are entirely too much for Mrs. Walker. When Daisy WILL not be cowed, the lady’s speech escalates from cool reasoning to barely contained fury. By the end of the scene we can practically see smoke pouring out of her. With the weight of society behind her, Mrs. Walker can definitely exert a certain dangerous power – at least on a social creature like Winterbourne. She absolutely impels him away from Daisy and into her carriage. There’s very little she won’t consider doing – but only so much she CAN do without upsetting her own apple-cart. Brennan does it all up with venomous flourish. A study in seething –but very well-groomed – frustration.

Brennan’s role climaxes with the carriage scene. Ostensibly, she’s out to save Daisy from compromising herself. In fact, she’s in hot pursuit of Winterbourne, propelled, in part, by that urge that makes us want to actually witness the thing that’s most galling to us. And of course, she means to stop Daisy - come Hell or high water – from once more rocking the boat. But Daisy’s pert-mouthed indifference, coupled with Winterbourne’s obvious infatuation, are entirely too much for Mrs. Walker. When Daisy WILL not be cowed, the lady’s speech escalates from cool reasoning to barely contained fury. By the end of the scene we can practically see smoke pouring out of her. With the weight of society behind her, Mrs. Walker can definitely exert a certain dangerous power – at least on a social creature like Winterbourne. She absolutely impels him away from Daisy and into her carriage. There’s very little she won’t consider doing – but only so much she CAN do without upsetting her own apple-cart. Brennan does it all up with venomous flourish. A study in seething –but very well-groomed – frustration.She does return at the end for a prominent appearance at the funeral. But she’s not there to mourn. Rather, to put a period on Daisy’s inconvenient story. Another hole in the dike has been successfully plugged. To Mrs. Walker, Daisy’s death is not a tragedy. Just another confirmation that failure to keep up appearances leads to inevitable doom. Actual – and more importantly – social.

No comments:

Post a Comment